Abbreviations: SI = Small Intestine; LI = Large Intestine

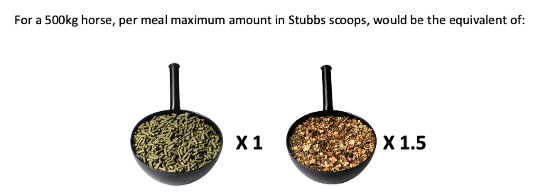

*all measurements and volumes stated are for a 500kg horse

Warning this article contains dissection images of the equine digestive tract

Like most topics, the more you know about the mechanics behind how something works, the more able you are to understand and manage them. This is certainly the case with the equine digestive system; equipping yourself to make informed and appropriate feeding decisions.

In this article we are going to take a journey through the horse’s digestive system from nose to tail, discussing how each section works and how this links to practical feed management.

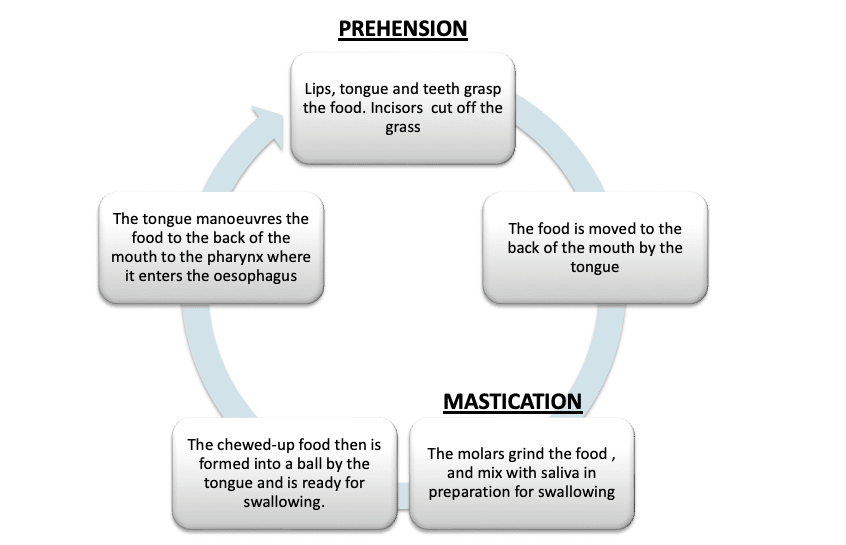

The mouth and teeth have two main functions; to chew food and to wet food with saliva. While no digestion or absorption happens here, our food starts its journey with mechanical breakdown. The horse grinds the food down into smaller particles creating a larger surface area on which chemicals and enzymes can later act 2 .

Here we can see more clues which evidence the horse’s evolutionary design for high fibre diets. Firstly, in their dentition, horses have what is termed hypsodont teeth, which means that they continually erupt throughout the horse’s life as the tooth surface is worn down. There are also differences seen in the number of teeth, horses have more molars and premolars than species which do not have a plant-based diet (like cats, dogs, humans) again to cater for a high fibre diet.

Secondly, the amount and timing of saliva production, and its contents, is again specific to the horse and his diet. Saliva production is key for the lubrication of food as it moves through the tract and contains ingredients (calcium, chloride, bicarbonate and sodium) 3 which provide buffering properties which (with a pH of 8.6-9.1 (alkaline)) 4 help to neutralise gastric juices in the stomach. Unlike other species, there is no significant digestive enzyme activity within saliva.

In horses, saliva production is triggered by the action of chewing 3,5 (perhaps an indication of their evolution to graze), whereas other species like dogs and humans can salivate on anticipation of food (a hint to these species being meal feeders).

When it comes to the quantity of saliva produced, this is dependent on the amount and type of food consumed 3,5 . Total chew time reflects food type and therefore quantity of saliva produced, for example, if you compare 1kg of hay to 1kg of oats, total consumption time would be 40 and 10 minutes, respectively, the former resulting in more saliva production. In addition to the duration of chew time, the moisture content of the food also has an impact on saliva production, drier foods stimulating more saliva than wetter feeds. On an average forage diet, a horse would perform 73-92 chews per minute 6 and produce an estimated 35-40 litres of saliva per day 3 .

Food is moved to the back of the mouth by the tongue to the pharynx where it enters the oesophagus, which conveys food to the stomach. The oesophagus is muscular tube, 120-150cm in length* through which food is propelled by a series of muscular contractions and relaxations called peristalsis. The oesophagus joins the stomach via a one-way valve called the cardiac sphincter which prevents regurgitation of food.

Food then enters the horse’s stomach, which is roughly the size and shape of a rugby ball, with a capacity of 8-15 litres 4 *. The walls of the horse’s stomach are inelastic as compared to our own which is elastic – another hint at the horse’s evolution as a trickle not meal feeder. Gastric acid is produced continuously (10-30 litres per day 7 ) here, in expectation of a steady trickle of food.

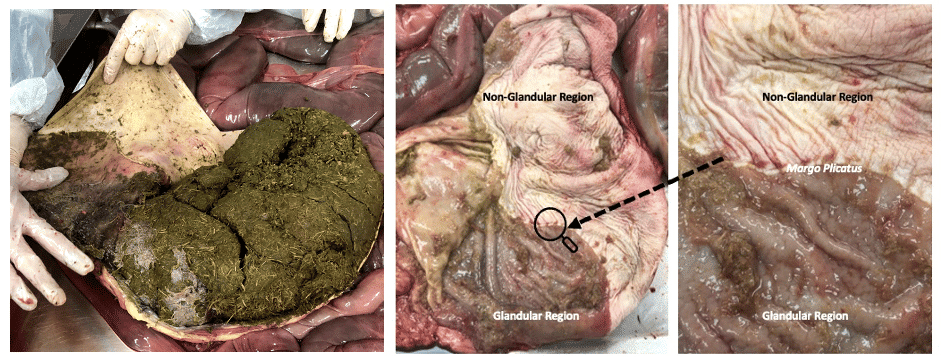

The equine stomach; left to right, digestive content of the full stomach; the empty stomach showing the Non-Glandular ‘unprotected’ (top) region and the glandular ‘protected’ (bottom) of the stomach and dividing line between the two regions, the Margo Plicatus

The horse’s stomach has two main regions, the squamous region, at the top of the stomach and the glandular region at the bottom of the stomach, the dividing line between the two called the Margo Plicatus. The glandular region contains glands which secrete pepsin and hydrochloric acid continuously for the breakdown of food but also has a mucosal layer secreting bicarbonate forming a protective layer to prevent acid from damaging the stomach lining.

The squamous or non-glandular region at the top of the stomach has no glands to protect the lining from harmful acid. This region acts as a reservoir for food as it makes its way to the glandular region. As there is no mucus or bicarbonate protection in the lining, this region instead relies on an almost continuous supply of fibrous material entering the stomach to act as a physical barrier against acid exposure.

What’s absorbed here?

The equine stomach is unable to hold large amounts of food (and functions most efficiently when only two thirds full), which links to our ‘golden rules of feeding’ , feed little and often. If too large a meal is fed, it simply passes through the stomach (and SI) more quickly, which does not allow sufficient time for food to be fully digested. If feed passes through the tract too quickly, this may lead to nutrients entering parts of the tract which are not designed to digest or absorb them. This can lead to issues such as diarrhoea and colic.

It is easy to see how continuous acid production coupled with saliva production, which is contingent on chew duration, can get out of kilter resulting in a more acidic stomach environment (the pH in a nearly empty stomach is 1.5-2). Saliva production and the presence of fibre in the stomach (acting as a physical barrier) are your horse’s natural inbuilt defences when it comes to stomach acidity, where these are not facilitated by management (i.e., insufficient forage, high starch intakes and long periods of fasting), there is increased risk of gastric ulcers.

With a total length of 30 metres (equivalent to three double decker buses!), a capacity of 150-190 litres, and transit (digestion) time of 24-72 hours*, the design of the horse’s digestive tract all indicate preference to diet containing harder to digest food (like plant matter) that takes a longer period to digest. The horse’s digestive tract is often referred to as two distinct sections, the foregut, which comprises the mouth through to the small intestine and the hindgut thereafter 1 .

The small intestine is named so because the diameter of this part of the tract is smaller (7-10cm*) than that of the large intestine, however, confusingly, at 15-22m length* it is significantly longer! The small intestine is made up of three parts, the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum and is designed for maximum absorption, with folds in the mucosal walls, villi and microvilli increasing the available surface area.

The rate of digestion of soluble carbohydrates (starch and sugar) in the SI means that after a high starch/sugar meal glucose is released into the bloodstream and can be used as a source of energy. Therefore, feed ingredients high in these nutrients are known as quick release energy sources and can lead to unwanted behaviour in some horses.

The large intestine is commonly referred to as the hindgut and is around 7.5-8 metres in length*. It has a huge capacity of over 100 litres* and represents over 60% of the horse’s digestive capacity. The large intestine hosts a population of microbes that are responsible for the digestion of plant matter (fibre like hay/haylage/grass/alfalfa). It is made up of three parts:

Material passes from the ileum (end of the SI) through the ileo-caecal valve and into the caecum. The caecum is a comma-shaped blind-ended sac which acts as a holding chamber and fermentation vat where fibrous parts of food are mixed with micro-organisms.

In horses with a healthy microbial population, structural carbohydrates (fibre) are converted to volatile fatty acids (VFAs; acetic, propionic and butyric acid). Digesta then passes into the large colon where the presence of bends slows passage and allows for the absorption of water and electrolytes. Finally, digesta progresses to the small colon where faecal balls are formed within sacculations (shaped part of the small colon which segments the faeces), which are then passed out through the rectum.

The slow rate of microbial fermentation means that fibre releases energy to the horse gradually which is why it is known as slow-release energy.

Any changes in feed type and ratio of concentrate to forage should be done gradually to maintain a healthy bacterial population. This links to another of our ‘golden rules of feeding’, make changes gradually. The number and type of micro-organism reflects the horse’s diet, each micro-organism usually only fermenting one food type. If sudden dietary change occurs, this does not allow sufficient time for micro-organisms to adapt, resulting in reduced digestive capacity.

Large feeds which result in overflow of starch and sugar into the large intestine, disrupting the pH 4 and resulting in the death of fibre fermenting bacteria should be avoided. For the microbial population to work optimally, it is key that the environment in the large intestine is conducive. Fibre-digesting micro-organisms favour a pH of around 6, any change in this towards a more acidic pH (which can be caused by excess starch and sugar entering the hindgut), will favour lactic acid producing bacteria which proliferate quickly resulting in poor fibre digestion and potentially hindgut acidosis.